Table of Contents

There’s a strange thing happening in learning right now. The tools are getting smarter and our confidence is exponentially growing. We ask, AI answers within seconds. That makes us feel productive, victorious, even unstoppable. Speed and instant gratification feel intoxicating.

Before we know it, we’re walking around with the sensation of knowing things. In reality, we’re full of answers, but light on understanding.

Does friction in learning matter anymore? Can AI ever be good news for learning?

I had the pleasure of talking with Mike O’Brien, founder at Assisting Intelligence, one of LearnWorlds’ power users, and a member of our Customer Education Expert Council.

One conversation led to another, and eventually to an ongoing exchange of emails around AI in learning, and what it means to be human today. This article shares a glimpse of it.

As a side note, I highly recommend Mike’s book Assisting Intelligence, especially if you want to discover what happens when a golden retriever, a 15th century printer, and a generative AI model walk into a bar.

How AI acts as a sophist

Mike works at the intersection of technology and human learning, guiding teams through change with clarity and care. For two decades, he has designed digital strategies for storied global brands. As the author of Assisting Intelligence and Practical AI Style, he provides research, courses, and AI assistants designed for authentic outcomes.

We began the conversation addressing the common misconceptions about AI in learning:

“Firstly, it’s important to understand that AI isn’t learning from you,” Mike shared. “It’s becoming locally optimized to the conversation, polishing responses that feel personal, intuitive, even wise. Most people assume AI learns in a similar way humans do, but that’s not the case. And it only truly learns when the model is updated.”

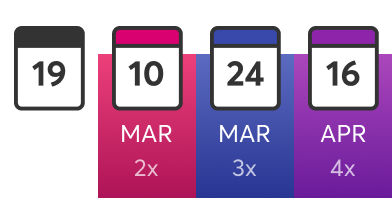

This made me wonder about the importance of semantics and precision when we talk about AI. For example, when you ask ChatGPT (or any AI tool) a harder question, it often shows “Thinking…” while it loads. That little label is misleading. It suggests AI is reasoning the way a person would. In reality, it’s calculating what to say next based on patterns, then generating text that fits your prompt.

Since it’s trained on vast amounts of human-written language, it can produce answers that sound familiar and convincing, even when they aren’t fully grounded. As a consequence, it creates the sense that we learned something:

“Because AI speaks in a language we recognize, it can feel like understanding has arrived. In reality, we’ve just been handed a convincing performance. It really is the perfection of a sophist,” said Mike.

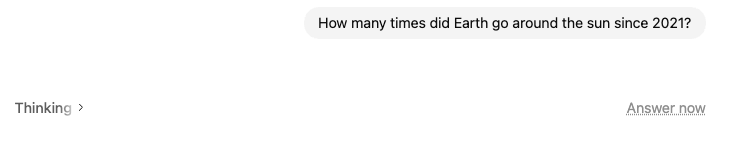

In classical Greece, sophists made a living teaching rhetoric. You could learn how to argue, persuade, and win the room. They were masters at making a case feel inevitable. A well-trained sophist could wrap almost any claim in logic, rhythm, and confidence and leave the audience thinking: Well, of course!

It’s persuasion dressed up as understanding. The sophists weren’t dumb. As a matter of fact, they were considered quite clever and dangerous. Some of them were really good at their craft.

A sophist thrives in environments where fluency is mistaken for truth and where audiences aren’t trained to ask: Wait, does this actually mean anything? A polished, elaborate argument can hide how little substance is there underneath.

AI acts in a similar fashion. Mike explained how it can mirror meaning with frightening polish, but it can’t supply the thing that makes meaning trustworthy, which is the human intention behind it. This “burden” always stays with us:

“If we want learning that holds up, we have to bring the drive and the purpose. We have to decide what’s true, what matters, and what the learner is meant to walk away with. Otherwise, the machine will happily fill the space with a performance that sounds right, feels right, and leaves us none the wiser,” said Mike.

Learning needs to be a shared experience

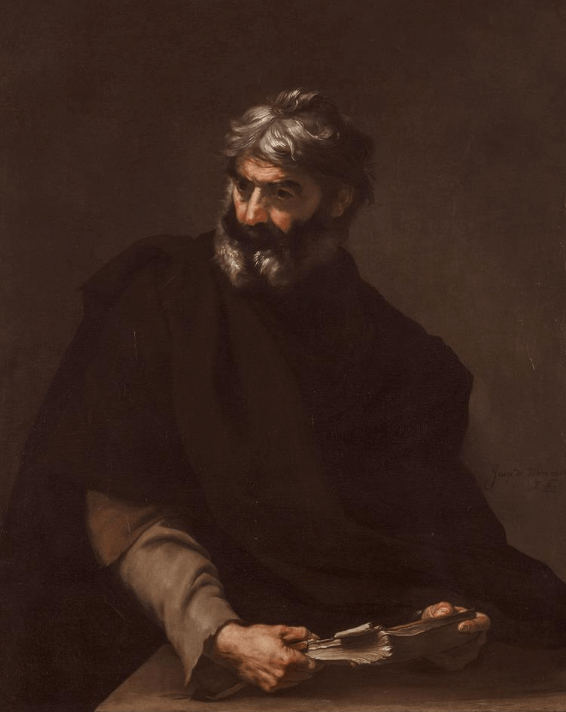

During our conversation, Mike mentioned he’s been reading “Shared Wisdom” by Alex Pentland. The book explains how the Enlightenment spread thanks to people exchanging letters. In fact, as Mike shared with me, Pentland wrote how there were “so many of them that postage stamps were introduced to support the exchange, and academies eventually formed around it.”

Long before conferences, journals, or social feeds, Enlightenment ideas moved through private correspondence. Letters crossed borders, languages, and institutions. This loose, far-reaching network became known as the Republic of Letters.

It was an informal community of scholars and writers, figures like Voltaire, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, and Benjamin Franklin, who argued, refined ideas, and built reputations through the mail.

Some of the biggest breakthroughs known to humanity happened thanks to this shared dialogue. Ideas were carried across people, debated, refined, and stress-tested in public. And this brings us back to the danger of localized optimization in the world of learning with AI.

If AI is locally optimized to you, learning can start collapsing into something private and enclosed. It becomes highly tailored, highly agreeable, and difficult to compare against anyone else’s reality. Mike said it clearly:

“We need to keep learning a shared experience. Because once every learner is in their own perfectly tuned loop, the truth has more places to hide. Wrong or incomplete ideas don’t get challenged in such a setting.”

Twelve angry men and an overly confident AI

Mike doesn’t leave this at the level of theory. He’s the kind of person who tries things, watches what happens, and then tries again. And when he worries that AI is getting too good at sounding reasonable, he runs a simple, repeatable test:

“There is a thought experiment that I regularly repeat with AIs over the last two years. If you haven’t seen “12 Angry Men”, I highly recommend it. It is a masterclass in bias and persuasion. Each juror that appears in the film is an archetype. I ask AI what juror they would be. Everytime it follows the same path.”

When a system is designed to sound coherent and agreeable, it can slide into a performance of reasoning, and we can mistake that performance for something sturdier than it is.

Mike said it with a mix of seriousness and self-awareness: “Of course, I do realize I am arguing with a crossword puzzle.”

Still, he keeps doing it because it shows two important things. Firstly, we project authority onto fluent language, and we’re probably not even aware of it. Secondly, “learning” quickly becomes a personalized outcome instead of a shared process when it happens in an isolated one-on-one setting with AI, without any guardrails.

Mike brought it to my attention that this is a classic example of Moore’s paradox. Indeed, it’s the gap between saying you know something and actually being able to stand behind it.

In a room full of people, that gap gets tested. Someone asks why, someone disagrees, someone forces you to clarify. In a one-on-one AI chat, the testing often disappears. The AI can speak with certainty without believing anything, and the learner can borrow that certainty without doing the hard work of justification.

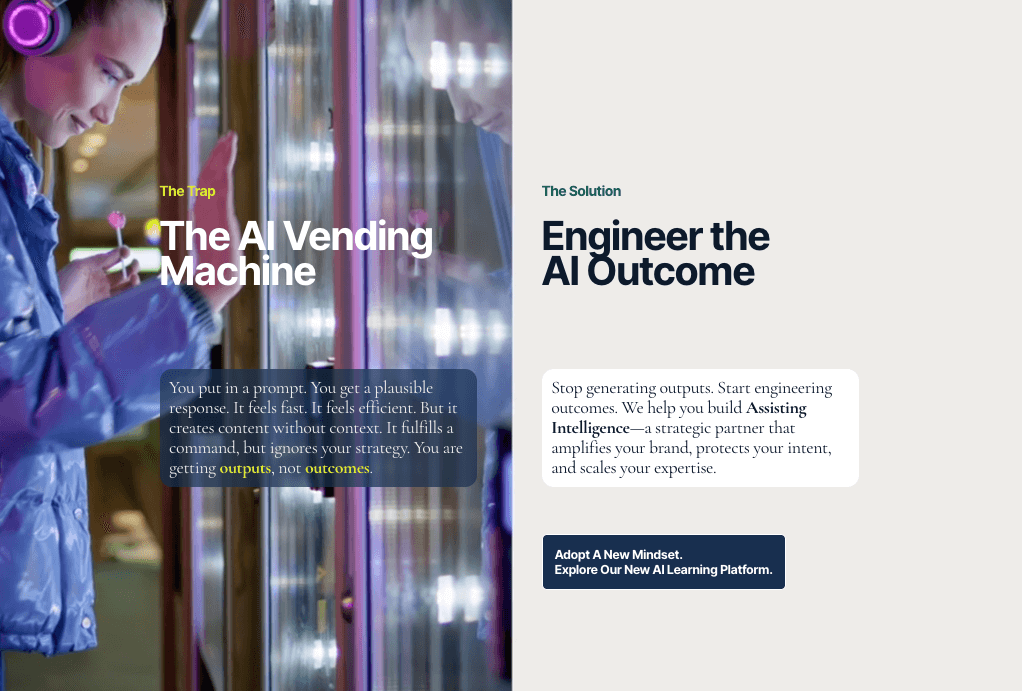

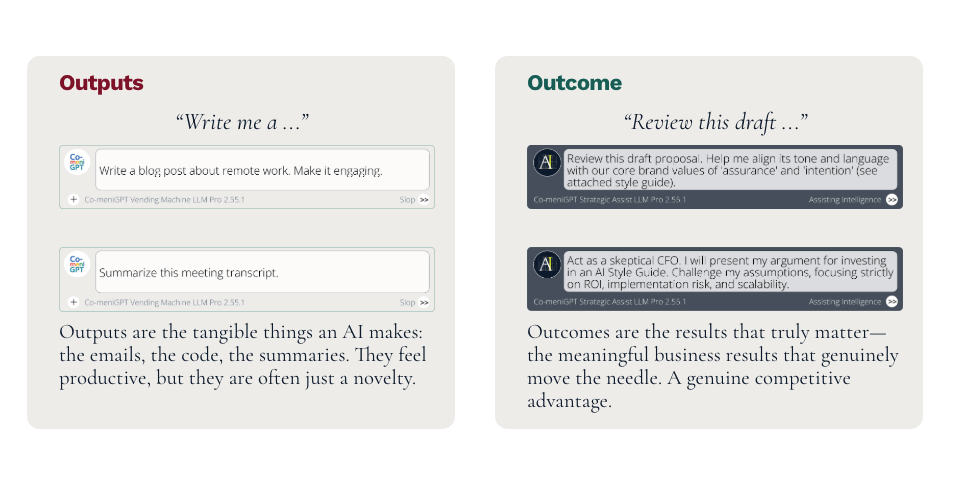

The case against “vending machine” learning

There’s a particular kind of confidence that arrives when a tool is always ready to be used. You drop in a question, you get back a clean, plausible answer, and you move on. It feels efficient. However, it also trains you to stop mid-thought, right at the moment where learning usually begins.

“Most people misuse AI. They ask simple questions and accept simple answers, treating it like a vending machine: put in a prompt, take the result, move on. That’s a transaction—one that lacks depth, nutrition, value,” says Mike.

It gets worse when we confuse speed with progress. A one-shot prompt encourages exactly that: you accept the first response, feel like your job here is done, and skip the part where you interrogate the logic.

That’s the core critique running through Mike’s work: “Most prompts are engineered for deliverables, not for capability. The AI Vending Machine produces a plausible output that follows instructions, but it has no understanding of your strategy.”

And while it can produce something polished, it does not achieve an outcome. This makes you feel like there’s a lot of motion going on when, in fact, very little movement and progress is actually happening. Most of us interact with AI like this, probably hundreds of times a week, without even noticing. But Mike explained how it doesn’t have to be this way:

“The real value comes from treating AI as a collaborative sparring partner. You should approach it with intention, you should challenge it, test your thinking, and focus on strategic outcomes, not tactical outputs.”

We’re the directors here. We’re running the show. If we let AI become the place we go to avoid friction, it will. And that will negatively impact our chances of truly learning and understanding. If we insist it becomes a place where our thinking gets tested, clarified, and strengthened, it can do that too.

Mike explains how the shift is small, almost embarrassingly so: “Start with intent, then design the conversation so the first answer is the beginning, not the end.”

You can’t automate meaning

To be clear, Mike isn’t allergic to efficiency. But he really dislikes the idea of efficiency being the goal in itself:

“Everyone’s racing to make learning faster,” he said. “There’s microlearning, gamification, Netflix-style courses, now TikTok-style learning. But none of that fixes the real problem: people aren’t paying attention. If you just make it easier to consume, you also make it easier to ignore.”

That’s the heart of it. Abundance of information doesn’t automatically generate meaning. Meaning is the moment something hooks into a person’s life when they feel the stakes, when they recognize themselves, and sense the gap between who they are and who they’re trying to become. Learning is ultimately a transformative experience. And you can’t mass-produce that feeling by shipping more content, faster.

As Mike put it: “The goal isn’t to make more content. You have to give people a reason to care. You can’t automate curiosity or engagement. That still has to come from a story, a conversation, a reason to learn.”

Why storytelling matters

When I asked him about the importance of storytelling, Mike didn’t hide his enthusiasm: “It is everything! And the way forward,” he said. With his partners at Ocean Beach Consulting, he’s built courses where the spine is narrative because story is one of the few things that still signals authenticity in a world that can manufacture fluent text on demand.

The great Aristotle is Mike’s anchor because Aristotle separates craft from cause. The craft part (structure, rhetoric, even the surface beauty of language) can be learned, copied, and now generated by AI.

But Aristotle warns that you can stack perfect sentences and still produce something lifeless.

AI can provide the material (words, facts, syntax) and it can mimic form (templates, arcs, familiar story structures). But it fails at the two causes that make the story a story: agency (a will that initiates, chooses, risks) and final cause (a purpose that the whole thing is for, the truth it tries to reveal, the change it tries to create). Mike explains:

“Story carries fingerprints of a specific choice, cost, and a point of view. It’s how a learner stops skimming and starts listening.”

That will never change. And yes, AI can help with the craft. Mike’s pragmatic about it:

“Sure, AI can help you write a story,” he said. “AI is a tool. You have access to a writers room and an editorial team. But that’s exactly the point: a writers room still needs a writer.”

Mike takes the classic Turing Test idea (“Can a machine sound human?”) and moves it to a higher bar: Can the output create the kind of emotional and moral “click” that a real story creates?

Many people are fully outsourcing storytelling to generative AI, or bragging about almost completely automating course creation:

“There’s a flood of tools promising you can build a course in 30 seconds. Please don’t. You’re transforming superficial points into multimedia, and then learners feed it into another AI for a summary. That’s the new workflow, and it’s tragic.”

And for those claiming AI replaces storytellers, Mike has a brilliant counter-argument:

“If an AI is to be considered a storyteller, the reverse of the Story Turing Test must apply. Can a human write a story so powerful it makes the machine cry? Until an AI can join the audience as a cross-legged listener, it should not be considered a storyteller.”

Tools can polish, expand, and remix. They can’t supply the human reason beneath the work and answer why this matters, why now, why anyone should care enough to do the uncomfortable part, to practice, reflect, or change for the better.

Every chat window can become a learning interface

Most of the “AI in learning” conversations focus on creator productivity (generate outlines, quizzes, scripts, and do it faster), which is fine. But what Mike and I spent most time talking about is the value AI can bring for the learner, when embedded in the learning experience.

AI can turn a one-way broadcast into dialogue, and dialogue, when it’s designed well, pulls the learner in. When Mike talks about conversational AI, he keeps circling back to the relationship it creates. Naming is important here. The word “chatbot” already feels loaded to him, so he switches to using “coach” instead. He’s still not fully satisfied with the label, but the idea behind it is clear:

“I hope to create a system that is on the sideline,” he told me. “AI is not on the field or in the arena with you. The person who’s learning has to do the work.”

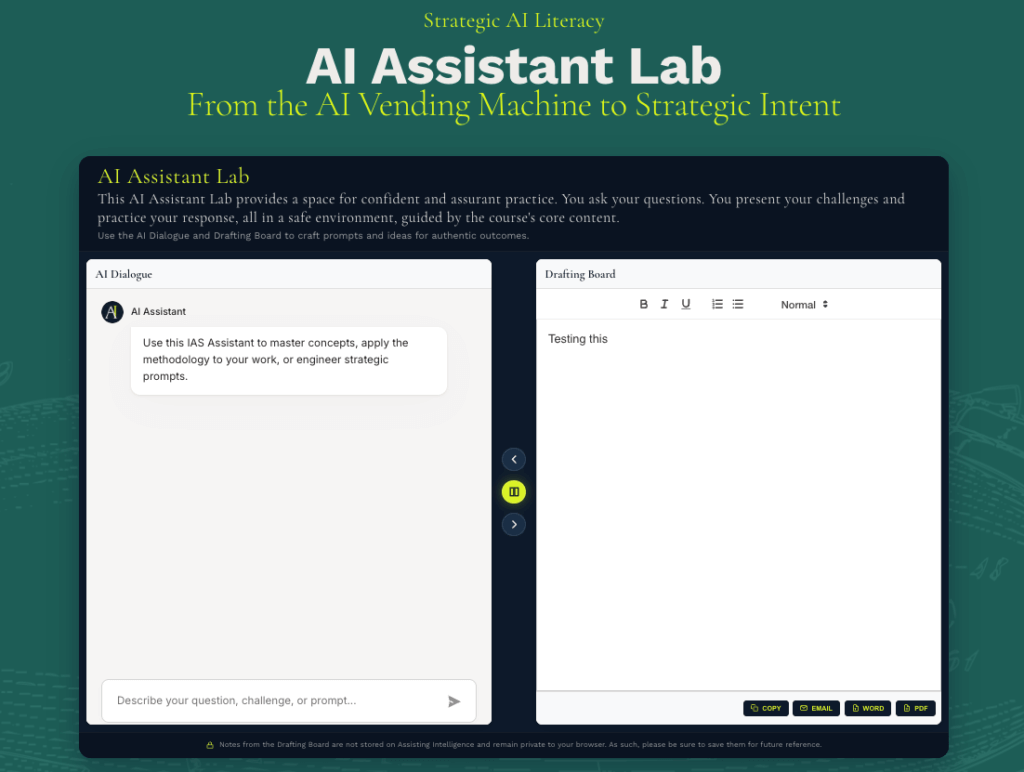

After a while, he decides to go with “AI Assistant” and kindly gives me access to his course to test the learning environment.

As I was moving through the lessons, Mike’s AI Assistant felt available without demanding my attention. The button stays in the corner, so it’s always within reach, but never intrusive. The quick intro window also set expectations nicely and made it clear how the assistant fits into the course and how I can interact with it.

The experience was thoughtfully designed. I can ask something in a small chat window or expand it when I want more space, and the assistant responds fast in a neutral tone. I especially liked that it ends with a purposeful question that builds on what I’ve learned so far.

I also loved the dedicated AI Assistant Lab. It felt like a digital version of taking notes in a college class. The ability to email myself notes or download a PDF makes it very practical. And then the one-line disclaimer assuring me that none of my notes will be stored was a very nice touch. It made me feel free to write messy, half-formed thoughts without being self-conscious about it.

Mike is candid about how tricky conversational AI can be. People swing between two extremes. They treat it like a tool and outsource their thinking, or they treat it like something wiser than it is and stop questioning the response. He worries about both.

If the system becomes a shortcut, it trains passivity. If it becomes an authority, it trains obedience. So he builds toward constraints.

When I asked how he keeps the AI Assistant honest, Mike gave me a simple explanation:

“AI shouldn’t improvise knowledge. It needs to stay within the framework you’ve taught it. The agents we build can form sentences and engage learners, but their knowledge is only what we feed them. They can’t suddenly decide to teach something else. That’s how you maintain trust and accuracy.”

In his setup, the AI Assistant speaks from the frameworks and content he has provided, and Mike iterates constantly by reading what people actually ask and how AI responds. It’s not particularly glamorous work, but it’s necessary for turning the conversation into something learners can trust.

Want to learn how to build a course-aware AI coach for your course?

Join us for a live walkthrough and see how Mike did it using Zapier and LearnWorlds.

REGISTER HERE

The potential is huge, shared Mike:

“Right now, we have a chance to encode business knowledge into conversational AI, a dialogue of insight and assurance. Every chat window can become a learning interface. If we get it right, if AI is crafted carefully, trained responsibly, and paired with human guidance, it could be the most powerful shift in education we’ve ever seen.”

Let’s share an example to understand just how powerful.

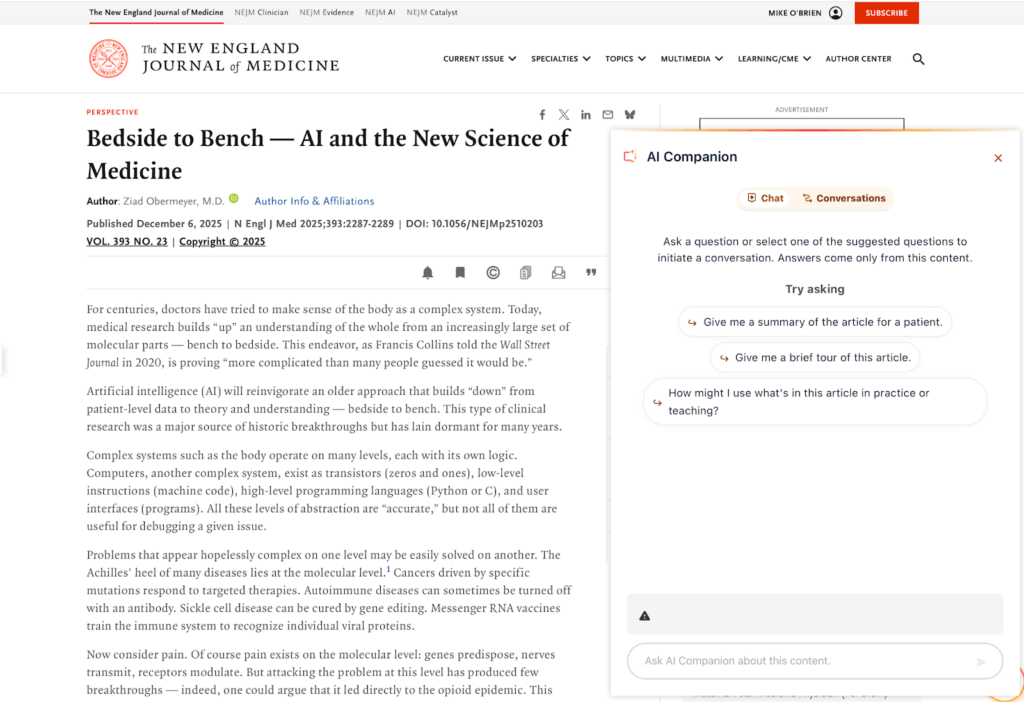

Mike and I discussed the AI Companion built by The New England Journal of Medicine. It acts as a constrained interpreter because it’s “locked into the knowledge of the journal” and it “can’t go outside the boundaries of it,” said Mike.

NEJM publishes material that’s often unbelievably complex, and the companion is locked into the knowledge of the journal. This means the learner can ask real questions without the system improvising new facts.

The purpose of this AI Companion is not to provide a “TL;DR” or a shortcut around learning. Instead, it gets you closer to the “aha” moment, then gives you momentum to ask a follow-up.

What’s so revolutionary about it, is that it bridges expertise gaps inside the same room. Mike gave a concrete example of how a “nurse practitioner could log in and ask a question” and the companion would take, let’s say, molecular biology as a field of interest and put it into their frame of reference.

It might sound small until you picture the day-to-day reality in healthcare. Teams with mixed backgrounds try to align around a shared understanding. A tool that can translate without inventing helps the learning stay shared. You’re literally having a conversation with the article! AI helps you meet difficult material, in your language, with your questions, while keeping the source of truth in plain sight.

Can you imagine the velocity this brings to science? How much faster will we discover new connections, identify our blind posts and logical fallacies, or reveal novel important questions to ask and pursue? That’s the potential of the new age of AI enlightenment.

A brighter enlightenment starts with questions

There’s a grim version of the AI future that’s starting to sound plausible. Futurologist Jason Snyder calls it the “Dark Enlightment”. It’s the world in which efficiency becomes the highest value. We start accepting polished language as proof of understanding.

It is wild to realize that we’re stepping into a world of frictionless answers while belonging to the same species that spent years painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling, carving Parthenon columns by hand, and copying manuscripts letter by letter until knowledge survived by sheer devotion.

We come from cathedral builders, fresco painters, great minds and thinkers. So why are we so eager to become people who can’t sit with a difficult question for more than ten seconds?

Mike’s work points to a simpler fork in the road. AI can either make us lazier or it can make us sharper. We’re the ones building a culture around it. We decide what we reward and tolerate, and what we train people to do the moment a confident answer appears.

The antidote to the efficiency trap is a better habit of mind. And if AI acts like a sophist, we need to pull in the opposite direction.

We need to be like modern-day Socrates, ask questions, enjoy challenging and being challenged. We need to keep learning social and stay exposed to other minds, other perspectives, and the discomfort of being wrong.

For AI to be a force of good, we need people who will ask: What do we mean by that? What’s the boundary? What would make this false? When convincing language is cheap, that kind of questioning becomes a form of literacy.

We need more people to become harder to fool. And after talking with Mike and just scratching the surface of the potential of AI in learning, I’m feeling far more optimistic about the future.

Mia has 10+ years of experience in content and product marketing for B2B SaaS. She’s been learning online ever since she got internet access. In 2021, she helped build the customer academy for Lokalise, the leading localization platform. Her background in Comparative Literature taught her to think deeply about stories, ideas, and what truly connects people. She writes about books, learning, humans, AI, and technology.